The Failproof Matrix for Evaluating Fit Vs. Performance

In every startup, there’s always a strong performer who struggles to get along with their teammates. Think of the superstar engineer or high-earning sales executive who toes the line between a bad culture fit (at best) and toxic (at worst). I’ve met and worked with this person as both an operator and startup advisor, and rest assured, this person presents one of the most difficult challenges a founder has to deal with.

Here’s the dilemma: As a founder trying to drive great business outcomes, you’re torn between the long-term health of your culture and the short-term results this person is delivering.

I’ve experienced this crossroad repeatedly throughout my career and learned (the hard way) that it’s a challenge best dealt with head-on. Your culture is not static, especially if you’re an early-stage company. Every day, your culture is influenced by what you do or don’t do. Failure to deal with employees who aren’t setting the right example for the rest of the team will result in that behavior being implicitly encouraged, which is especially dangerous for your company’s long-term health.

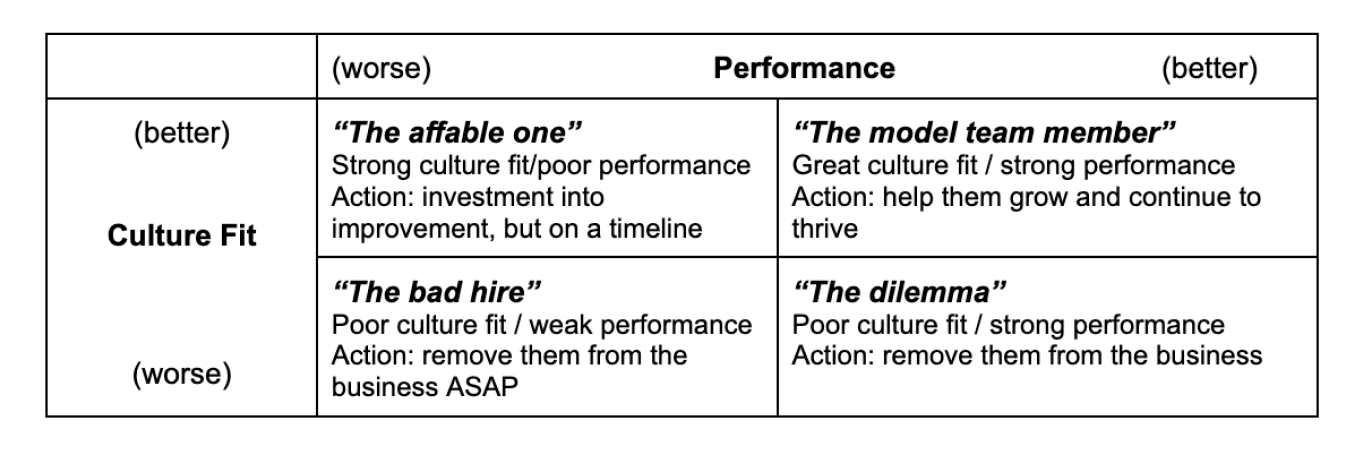

To help make these decisions easier, I’ve plotted a two-by-two matrix that’s worked with many founders and executives over the years:

Breaking down the quadrants

Like many two-by-two matrixes, the upper right and lower left quadrants are fairly straightforward.

Upper right: The model team member.

Your team ideally has many of these people. They are a great cultural fit and strong performers. These are people you should cultivate with stretch opportunities and grow. Call out and recognize their good outcomes and cultural alignment in front of others. Encourage your leaders to mentor and invest time in these people. They set examples for others on your team and are the ones you want to keep on board.

Lower left: The bad hires.

These folks are easy to part with. They aren’t doing the core job well and they are poor culture fits. Your company hopefully has very few (if any) of these people, and you are quick to spot and remove them if you do.

The upper left and lower right quadrants are where things get complicated.

Upper left: The affable one.

This person is sometimes someone who has been at the company for a long time but is no longer performing at the high standard needed as you scale. These people are beloved as cultural flag carriers, but their performance is leaving a little (or a lot) to be desired.

My recommendation is to invest in helping these people perform better. You could explore giving them access to professional coaching or mentoring from a high-performing team member. You can also consider a potential role change. For example, is a former salesperson now better suited for a customer success role?

Whatever you do to invest in these types, make sure you do so on a clear timeline. Otherwise, you are setting an example across your company that a good culture fit—but poor performance—is acceptable. If, within the clear timeline, the person is still not performing, you’ll want to exit them from the business. Do so professionally and generously.

Lower right: The dilemma.

This is the archetype that I find myself spending the most time talking to founders about. It’s the classic example of the salesperson who is crushing their quota or the engineer who is shipping the next big feature ahead of schedule, but the rest of the team can’t stand working with them. Sometimes, their behavior is out of line with what you expect from the rest of your team. So what do you do? I strongly believe that life is too short and culture is too important to work with people in “the dilemma” category. As hard as it may seem in the moment, I always recommend swiftly exiting these people from the company.

It’s important to note that members of your leadership team may make excuses for people in “the dilemma” category. This often comes in the form of artificial time constraints (“after this quarter,” “once we get past this release”). In the past, I’ve found myself making these types of excuses to justify keeping high-performing but culturally bad salespeople on the team for another quarter or two. I always regretted it later. There is never a “good time” to exit someone who is a high performer - it’s always going to hurt. Yet, if you keep these dilemmas on the team, you’re continuing to send a message to the rest of the team that their behavior is acceptable.

Exiting these people will be difficult in the moment, but your team will almost certainly recognize and appreciate your conviction as a leader by making the decision. In fact, your team will likely rise to the occasion and continue to make progress without a toxic employee holding it back.

I’ve seen this happen before. When making a difficult decision to exit a dilemma team member on one of my teams, the rest of the team recognized it was a hard decision and put in extra effort to help us meet our goals for the quarter. A quarter or two later, the team was performing even better than it was before, but without a team member detracting from the culture.

Regardless of stage, balancing culture fit versus performance will be a constant as your team grows and evolves. But as your company scales and more people join the leadership team, it’s important to create an environment in which all leaders are empowered to make these tough choices and decisions.

Doug Hanna is a revenue and operations executive who is a GTM Advisor at TheGP. Prior to TheGP, Doug was the COO at Grafana Labs, where he led all of go-to-market and operations as the company scaled from pre-Series A to post-Series D.

Up Next

Welcome Dan Pupius to TheGP

An update to our engineering bench

Partnering with VectorWare

We’re entering the GPU-native era.